Motion

Notes on taxis, movement, and change

2 a.m. Lanes glow with brake lights, strings of bright rubies. I’m in Hong Kong and the sight below is familiar. Every time I’ve been jetlagged here, I have looked out of the window and there have been taxis. At least one every few seconds, at least a glimpse of bumper disappearing into darkness. Tonight there are neat streams of them; they keep coming, pausing, going. I doze off, and two gauzy hours later, the roads are still a red blur. They just keep moving.

—

There’s been a lot of movement lately. To a new home, a new age. I’m visiting Hong Kong and yet I’m also in so many other places: 2025, limbo between a flat we’ve sold and a flat we’ll rent, the next point in my life. Change has swept past my face like a fast force in a cartoon, dishevelled hair and wide eyes left in its wake.

The new flat is not yet a home, and 35 is not yet a known space. It’s almost May, and this year is also not yet a known space to me. My emotions are in it and so is my body, feet pressing against pavement, but there’s a disconnect. Some kind of splicing. Twenty-twenty-five, two-thousand-and-twenty-five. I acknowledged the year with resolutions but it still feels bizarre. Implausible, like the way we talk about 2050. Only we are actually in 2025, almost halfway through. It has been leaden and pitchy already, and maybe that’s why I feel I don’t know it yet; I might not want to. Stay away from the stove after catching a finger on a flame, don’t engage. A survival response.

But I remember reading once that all movement is a departure. This is both a relief and a devastation. Every coarse moment, every sable mood, an exit. Every millisecond, every rise of the ribcage, a leaving. The kind of recent past so recent that my brain can’t fully comprehend it. In Constellations, Sinead Gleeson writes: ‘Departing requires leaving behind an old part of you.’ A relief and a devastation. Goodbye to

the me that imagined staying, replacing the fake granite counters with Japanese cypress. The me that believed we were ever the kind of people who would root ourselves in one place when we constantly bloom for elsewheres.

the slender belly that felt safe and held in my jeans. It’s back at the start of 34, back before the stress, back there with cells that worked quicker, smoother, tirelessly.

the year I had known. Its edges enveloped mine until we were folded together, not always soft and flush but known to each other at the very least.

All movement is a departure, but I try to remember that this means there is also a moving into.

—

I can recall so many taxi journeys. It’s such a specific circumstance: trusting a stranger in very close proximity—see the blue stitching along their jacket collar—to take you somewhere in an unfamiliar vehicle. My senses are always heightened: I recognise this smell / are those his children framed and dangling from the rearview mirror / I’ve never noticed that building before. Sometimes anxiety, but there’s mostly been joy. So many taxi journeys where I was laughing. Not a fruit of the destination that awaited but the moment of travel itself, a microcosm of life in motion.

On the cusp of adulthood, four to a car, these rides remembered much more clearly than those home. Hip wedged against hips wedged against hip on the backseat. Gossip exploding in the air, cackles as bright as fireworks.

In New York, the hotel called us a cab to the airport, and a white stretch limo showed up. Me and K in the back, tiny just this once, our legs short like matchsticks in the vastness. Swapped glances, skin crinkled around the eyes, flourishing into hysterics.

In a tuk tuk, my best friend’s voice vanished into the street din. Claggy air and car horns rushed into our open mouths as we moved them. All we could do was grin at each other through errant strands of our windblown hair and point as new things passed.

After a stressful sewing workshop, laughs of delirium, laughs in solidarity, my unfinished tote bag tossed onto the leather seat between new friends.

—

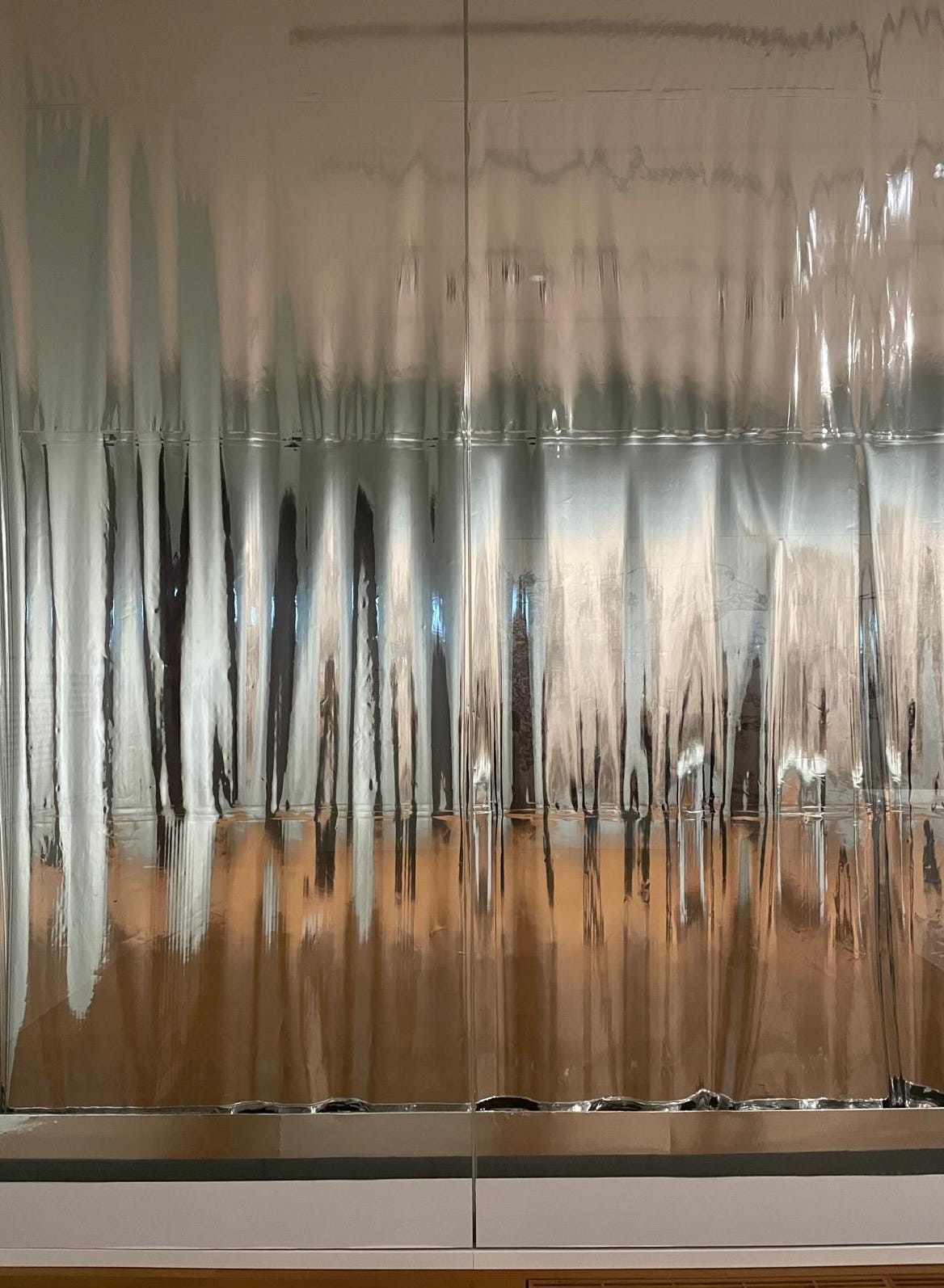

A thick mirrored fabric is hung behind the glass like a curtain. It’s Guo Cheng’s Becoming Ripples and, according to the placard, there is a preprogrammed kinetic system that triggers movement. The material reminds me of the aluminium protectors you unfold inside car windshields against hot glare but with the folds ironed out. I stand in front. It gently tremors, catching the light, and I become ripples. The movement is subtle but effective, makes me think of quiet oceans at dawn, makes me think of small waves of heat over concrete. My reflection is compressed and refracted across the waves, a dark vertical line, barely legible. I get closer to see more of it, and a gust blasts from the bottom left corner. The sheet panics, flails in the middle, I panic, step back. I’d become used to the soft undulation, as if there was no movement at all. Got lulled into the feathery rhythm without realising. But I’d been moving all along.

—

I rode the airport train to my hotel, quick and easy enough, but it was a sealed capsule speeding across a bridge in the sky. I book a taxi for my journey back to the airport. I need to know that I’ve moved, truly. To feel gravel rumble under the tyres in the back seat and see lights fuzz slow through the window. To arrive at a destination under no false pretences, in no confusion. To rearrive, at all these places I am inhabiting now.